What is the Power Footprint of International Organizations?

October 11th, 2021

It’s undeniable that international nonprofit organizations headquartered in the West hold a vast amount of power compared to local organizations in the “Majority World”. Systemic factors, such as colonialism and racism, have enabled international nonprofit organizations (INGOs) to increase their authority, control, and influence in multiple industries like humanitarian aid and global development. You might say that these NGOs have a large “power footprint.” Power itself is of course not inherently bad. All organizations need some level of power to drive change. But power can become menacing when centralized and rooted in a singular worldview. The result, as we’ve seen in the INGO space, is a Western-centric system that drives change in a foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric manner.

In contrast, the power footprint of local organizations tends to be smaller, more diverse, and less prone to groupthink. Their power is more firmly rooted in local expertise and lived experience, local ownership and local leadership. This is why the Power of Local often favors social solutions over technical solutions. That said, nonprofits with smaller power footprints are not inherently more effective than those with larger ones. Leadership and context matters just as much, but the cumulative impact of their often unintended consequences, or negative externalities, rarely reaches systemic proportions. This is less true of international NGOs since their outsized power footprints have an impact on the system itself. Naturally, the conceptual lines that distinguish international and local organizations can be blurry in reality.

So let’s think through what happens when an international organization implements a large development project. One consequence of such a project is the growth of the INGO’s power footprint. It takes power to make power. This does not make INGOs more effective. The more projects an INGO implements, the more they consolidate their authority, control, and influence, regardless of the project’s outcome. Either way, their power footprint remains largely invisible at this scale. We seem more interested in measuring the impact of individual INGO projects than in measuring the impact of the byproduct, i.e., the greater centralization of power within the international development space at the expense of local organizations. Measuring both types of impact is essential. But we rarely capture this negative externality of our foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric projects. It seems to us that ignoring the reality of power footprints is making our collective work on systems change and decolonization more difficult. How can we change what we don’t measure?

How do we measure our own power footprints to create more visibility and transparency? Can we co-create practical metrics to measure the power footprint of INGOs? Can we make the consequences or byproducts of said footprints more visible? Can we gain inspiration from other fields? How is the carbon footprint measured, for example?

We realize full well that measuring power footprints is a wholly different undertaking to measuring carbon footprints. Analogies can capture the imagination and serve as powerful metaphors, however. Heavy industries have significant positive impact by creating countless jobs and higher standards of living. Over time, however, the cumulative impact of large carbon footprints triggers a global climate emergency. In a similar vein, the massive power footprints of INGOs may be contributing to another global emergency: the pandemic of inequality. There’s lots to unpack here, so we’re working on a longer peer-reviewed piece that expands on these ideas and several other points that we don’t have the space to get into here.

In sum, we know that power is relational, complicated, and polarizing. We also know we've got to start somewhere. We need to co-create a transparent mechanism to make the invisible visible and ensure that the reduction of power footprints is real and not just symbolic. The alternative is to continue having the same conversations over and over without ever doing something to affect change.

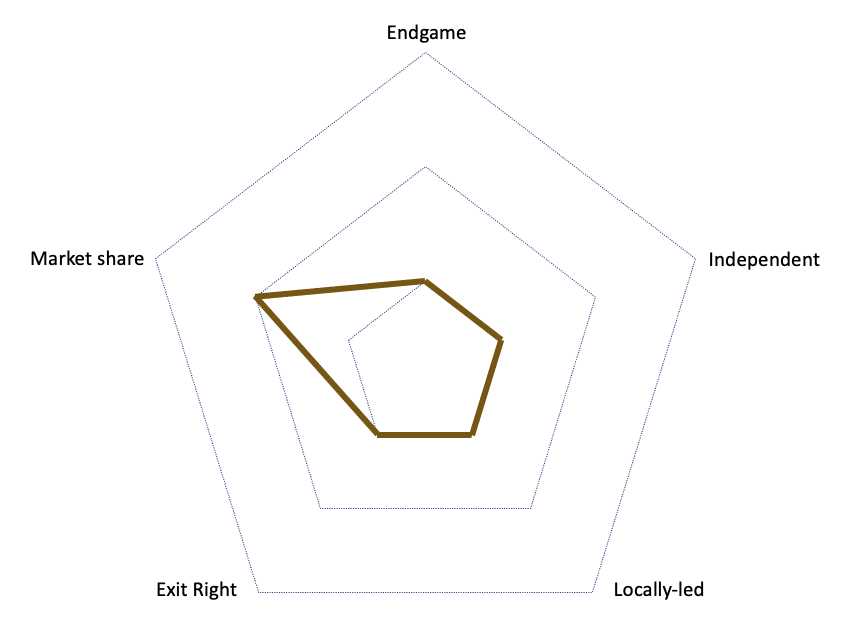

So we’ve developed 5 very preliminary metrics for illustrative purposes, and applied them to our own organization, WeRobotics. Each proposed metric is rooted in a question to ourselves, that can also be asked to INGOs:

- Are our country offices (or equivalent) independent?

- Are they locally-led?

- Can they exit at any time?

- Are we ceding market share?

- Do we have a clear Endgame or exit strategy?

One can then develop specific definitions for each of the keywords above, (i.e., independent, locally-led, exit, market share and endgame). Independent, for example, can mean that country offices” select their own staff, projects and partners (decision power). And/or that they are also financially independent from the INGO that originally co-created or established the country office. And one can then develop a point-based system to score and visualize the power footprint. For example, the answer to each metric question can be scored as 1, 2 or 3 points: Yes = 1 point; Somewhat, or In the Works = 2 points; No = 3 points. As an example, WeRobotics’ power footprint with such a metric system is displayed below.

Our power footprint appears to be particularly small, which is in line with our "Power of Local" strategy. On the other hand, one could claim that we deliberately selected metrics that make us look good, to which we reply: “This is an open call for help and collaboration to co-create truly objective metrics.” We’re not experts on power dynamics. We know that others have studied power for many more years than we have, decades even. We want strong metrics and we are fully committed to taking the Power Pledge: actively measuring and reducing the power footprint of our own organization. So we want to learn from a diverse range of experts by catalyzing an open collaboration on the power footprint. This is about making international development organizations more effective. So please get in touch if you’d like to participate in this co-creation process.

Recent Articles