The Dangers of Foreign-Led, Top-Down, Techno-Centric Solutions

February 1st, 2021

We founded WeRobotics to counter the foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric mindset that pervades the so-called "technology for good" space. We counter this mindset by shifting power with local experts, primarily across the Flying Labs network. Many have already written extensively about the dangers of foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric solutions over the decades. So we're focusing more on writing about The Power of Local: the positive and sustainable impact of locally-led solutions. That said, it behooves us from time to time to share concrete examples of the destructive impact that top-down mindsets have had. Otherwise, we run the risk of making vague, sweeping statements without pointing to concrete evidence.

One of the worst examples of foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric projects we've encountered began half-a-century ago in Bangladesh. In the early 1970s, the vast majority of Bangladeshis lacked access to clean water, which contributed to numerous diseases that claimed hundreds-of-thousands of lives each year. So UNICEF launched a "nationwide program to sink shallow tube wells across the country. Once a small hand pump was installed to the top of the tube, clean water rose quickly to the surface." By the end of that decade, more than 300,000 tube wells had been installed, and some 10 million more went into operation by the late 1990s. With access to clean water, the child mortality rate dropped by more than half, from 24 percent to less than 10 percent. UNICEF's solution was thus "touted as a model for South Asia and the world."

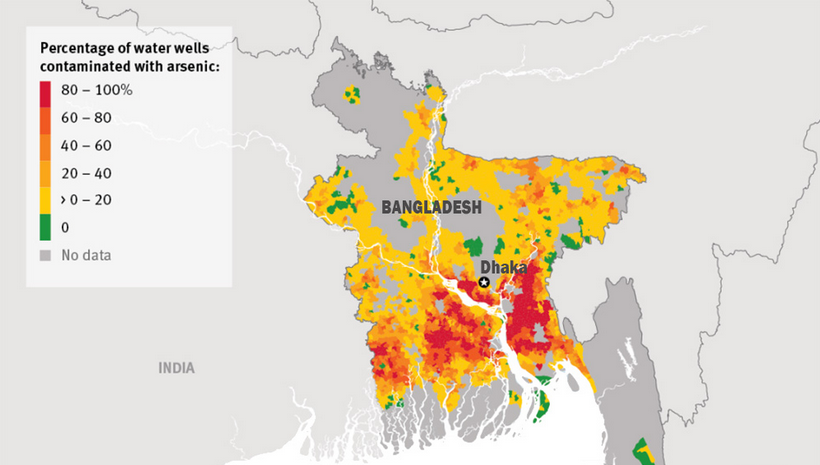

However, in the early 1980s, signs of widespread arsenic poisoning began surfacing across the country. "UNICEF had mistaken deep water for clean water and never tested its tube wells for this poison." WHO soon predicted that "one-in-a-hundred Bangladeshis drinking from the contaminated wells would die from arsenic-related cancer." The government estimated that about half of the 10 million wells were contaminated. A few years later, WHO announced that Bangladesh was "facing the largest mass poisoning of a population in history."

So the World Bank funded an intervention to paint each well's spout red if the water was contaminated and green if safe to drink. Five years and over $40 million later, the project had only been able to test half of the 10 million wells. "Officially, this intervention was hailed as almost instantaneous success." But the widespread negative socio-economic impact and community-based conflicts that erupted from this one-off, top-down intervention calls into question the purported success of this intervention.

Water use in Bangladesh (like many other countries) starts and ends with women and girls. "They are the ones who will determine if a switch to a green well is warranted because they are the ones who fetch the water in water numerous times a day." The location of these green wells will largely determine "whether or not women and girls can access them in a way that is deemed socially appropriate." As was the case with many of these wells, "the religious and cultural norms impeded a successful switch."

Also, "negotiating use of someone else's green well was an act fraught with potential conflict." As a result, some still used water from red-painted wells. In fact, "reports started to come in of families and communities chipping away at the red paint on their wells," with some even repainting theirs with green. Such was the stigma of being a family linked to a red well. Indeed, "young girls living within the vicinity of contaminated wells suffered from diminishing marriage prospects if they were able to marry at all." And because the government was unable to provide alternative sources of clean water for half of the communities with a red well, "many women and girls returned to surface water sources like ponds and lakes, significantly more likely to be contaminated with fecal pathogens." As a result, "researchers estimated that abandonment of shallow tube wells increased a household's risk of diarrheal disease by 20 ."

In 2009, a water quality survey carried out by the government found that "approximately 20 million people were still being exposed to excessive quantities of arsenic." And so, "while the experts and politicians discuss how to find a solution for the unintended consequences of the intervention, the people of Bangladesh continue bringing their buckets to the wells while crossing their fingers behind their backs." A new study published in 2020 reported the following: "Today, despite a much-improved well water testing effort, an estimated 30–35 million are still chronically exposed to elevated levels of As in their drinking water, and hundreds of thousands are suffering from cardiovascular disease and cancers, leading to a staggering annual estimated death toll of 43,000."

This series of foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric interventions in Bangladesh led to the largest mass poisoning in human history. "Chronic exposure to arsenic causes arsenicosis and may include multi-organ pathologies. Many of the health effects of chronic toxicity are evident in Bangladesh. Besides dermatological manifestations, non-communicable diseases, including cancer, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and decreased intelligence quotient among the children, are increasing... Due to long-term low-dose arsenic exposure through consumption of contaminated water, is now an important concern of Bangladesh as it increasingly reported from arsenic-exposed individuals."

Unfortunately, there are plenty more examples of how top-down thinking has resulted in large-scale projects' failure, many of which have caused direct harm, like in Bangladesh. An excellent place to start to learn more is James Scott's book, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. The trouble is that only the most destructive of these large-scale interventions tend to be documented in books and investigated by the media. In other words, there's a long tail of much smaller top-down projects that have failed but are rarely, if ever, investigated or publicly documented. When aggregated over time, this long tail of failed projects may well be causing just as much harm as more extensive projects.

We founded WeRobotics to counter the foreign-led, top-down, and techno-centric mindset that results in harmful social good projects, regardless of how large or small these projects are. By partnering with local experts with a deep understanding of the local context, projects benefit from local buy-in and participation and avoid the (sometimes catastrophic) pitfalls of arrogance or ignorance.

References for the citations and images above:

Recent Articles